Transport

Different means of transport were vital to the development of the sand industry in and around Leighton Buzzard.

To begin with, sand was moved by horse and cart along the roads through the town to be sold for local use, for example by building firms and in tile-making.

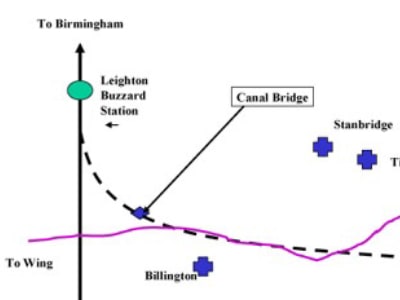

With the advent of the canal in the early 1800’s, there was access to a wider market and carts moved sand from the quarries to be loaded into boats at Arnold’s Wharf, Old Linslade and at Black Bridge near Tiddenfoot. The sand could now be taken south to London or north to the Midlands.

Similarly, the coming of the railway in 1838 opened up many more opportunities to transport the sand throughout the country. However, the constant passage of carts through the town caused such damage to the roads that the Council demanded that the sand firms set up an alternative form of transport.

This led to the building of the Leighton Buzzard Light Railway in 1919, which became the main means of moving sand from the quarries in the north of the town to the southern outskirts. Here were situated the grading and washing sheds with easier access to the canal and the mainline railway.

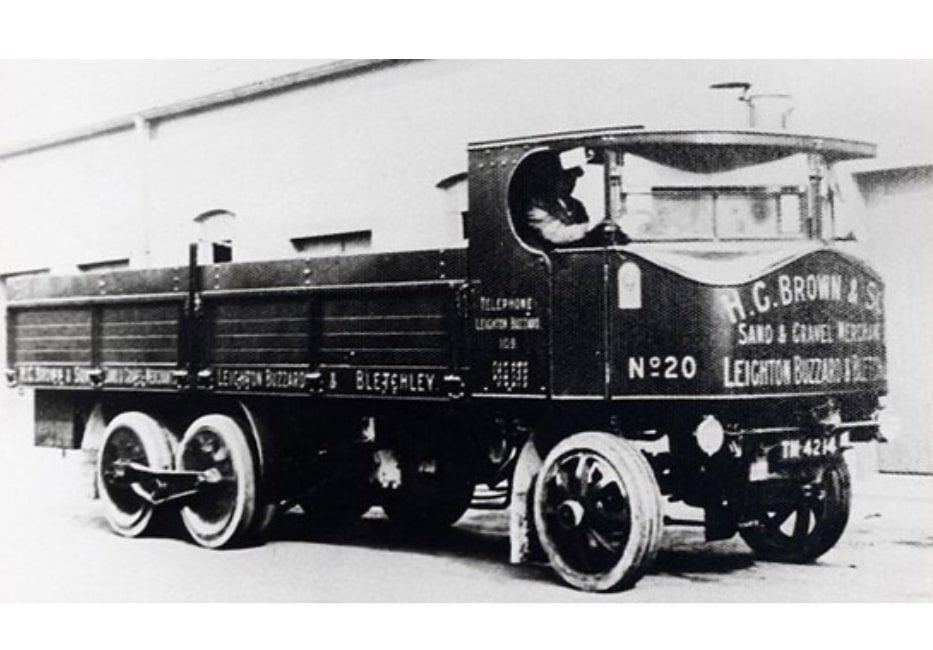

Transport by rail declined in the years following the Second World War and was replaced by road haulage. Lorries could deliver faster and more directly and so, from the late 1950’s onward, Leighton Buzzard became home to many haulage firms, most of them involved in the transport of sand or of its associated products.

Canal

The coming of the Grand Junction canal (Grand Union) to Leighton in September 1800 changed the geography of old Linslade considerably. Early boatpeople were still using the canal side church of St Mary’s at Old Linslade and J.Arnolds (pit owners) were loading sand at Sandhole bridge (B110) north of what is now Leighton Buzzard. New industries and wharves were quickly developing further south on the canal where the modern town is now.

In 1792 a well-attended meeting of canal investors was held in Stony Stratford with strong support from the Marquis of Bedford, who eight years later greeted the first boats to pass through Leighton from Tring on route to Fenny Stratford. Linslade had already been influenced by the coming of the canal with a large influx of itinerant labour (navigators) and their families, craftsmen to build the bridges and aqueducts and locks and surveyors and overseers to manage the “Grand Canal”.

Canalside industries consisted of limekilns, coal and grain merchants, engineering companies, haulage and packet boat companies as well as the administrators of the canal such as wharfingers, lockkeepers, canal police, lengthmen and toll clerks.

Local sand producers did not start using their own boats until the 1890’s when wide beam boats (wider than seven feet) were introduced. As the numbers of boats increased, narrow boats replaced the wide beam and engines replaced the horses.

Arnolds loaded their boats from a northerly wharf close to bridge 110 which served their pits in the Heath and Reach area. Transport was always by road using carts but sand was also moved by rail to Sheep corner (Heath and Reach) and then loaded into carts. Later lorries were used.

By the early 1900s sand of all grades was regularly shipped to London and the Midlands and a peak tonnage of 40,000 tons was shipped south in 1912. Garside’s alone shipped a total of 17,068 tons in 500 boatloads in 1912. But steadily, rail and road transport reduced canal use and Arnolds finally gave up using boats in the 1930’s whilst Garside’s continued into the 1950s, which was also a period of national decline in the canal system.

An Aylesbury canal haulier, Arthur Harvey-Taylor, continued sand shipments to Paddington and in 1952 1,470 tons was moved using five pairs of boats. By 1962 only 800 tons was being moved by the Barlow carriers and the sand was now moved to the wharf by road transport following the closure of the Light railway in the early sixties.

Canal transport of sand had provided early employment for William Vaughn of Friday Street, Leighton, in 1929, when he worked with his father on horse drawn canal boats belonging to Garside’s and later worked for A.C.Biggs, a local road haulier, still moving sand around the country.

The final shipment of Leighton Buzzard sand was in April 1965. Twenty-five years later in June 1990 an enactment was carried out with sand being tipped from original light railway skips into N/b Archimedes, an ex. Grand Union Canal Carrying Company boat, moored alongside Garside’s old wharf at Tiddenfoot.

Today, commercial canal transport is still alive in several parts of the country.

Canals GALLERY

Tap an image below to view

Railway

By the 1830’s, 1000 tons of goods were being sent by canal from Birmingham to London.

It was slow and demonstrated the need for a railway link between the capital and the industrial midlands. This would be the first trunk railway to be built in the whole world. The journey time from Birmingham to London became six and a half hours by train; compared with 13 hours by stagecoach.

The London to Birmingham Railway is 112 miles long. Build cost per mile £50,000, five years to construct, labour force 20,000 men. It was built and opened in stages. The Tring to Denbigh section, which included Leighton Buzzard, opened for traffic on 9th April 1838 and the whole line from London to Birmingham was completed in October 1838. (Queen Victoria’s coronation took place on 28 June 1838).

The joining up of Leighton and Dunstable by rail resulted from the plan devised by George and Robert Stephenson after the people of Luton rejected the idea of joining their town and Dunstable by rail. An Act of Parliament in 1845 allowed the go ahead, the line was eventually opened to both freight and passengers in June 1848 and was operated by LNWR (London and North Western Railway)

Coal was offloaded from canal barges onto trains and the laden wagons took it to the gasworks in Dunstable and picked up chalk and lime from the Tottenhoe quarries and Sewell lime works on the way back.

Other freight traffic was light; some farm produce and animals. As freight in and out of Leighton Buzzard grew and the sand industry expanded, a sidings was built at Grovebury. Land was purchased south of the station for more sidings and a goods facility which opened in 1874. It was known as Wing Yard. Freight trains backed up from the sidings to Leighton Buzzard and then onto the main line.

As the Branch Line grew in importance, six private sidings were built between Billington Road crossing and Grovebury crossing. By 1858, the line was extended to Luton and the passenger traffic increased as workers travelled from Leighton Buzzard and Dunstable to the factories in Luton. In 1860, a line opened from Luton to Welwyn.

Grovebury Sidings was a large railway freight depot near Leighton Buzzard, where sand from the local pits was transferred onto freight trains at Billington Road for onward transport via the main line to the Midlands and south to London. It was carried to the sidings by road, on carts hauled by steam tractors, which caused congestion on the roads and a constant need for road repairs. Sand quarry owners had to pay a toll for the carriage of the sand by rail, which was one penny per ton per mile.

The sand industry was given a tremendous boost in 1914, when, with the invasion of Belgium by the Germans, the import of sand from abroad ceased. During World War One (1914 to 1918), the munitions industry required quantities of good quality sand for bomb casting, and the output from the Leighton Buzzard pits was stepped up to meet the demand.

In 1919, the Leighton Buzzard Light Railway was opened for carrying the sand to Billington Sidings. The narrow gauge wagons of the light railway were shunted alongside the standard gauge wagons and the sand tipped directly into them using an“L” shaped double track gantry.

By the 1930s, there were seven sand trains (a total of sixty to seventy wagons) a day leaving Grovebury Sidings and onto the main line. The amount dwindled as sand began to be carried by road on lorries.

World War Two however brought a similar increased need for sand and as petrol for the lorries once again became scarce, once more rail became the cheapest and best way to carry sand. Between 1950 and 1957, British Rail built 1000 new wagons to cope with the transport of the sand and gravel from the pits in the area.

The British Rail Strike of 1955 lasted seventeen days; sand from the quarries was forced onto the roads. With the opening of the motorways in England, especially the MI in 1959, quarry owners looked more and more to moving sand by road rather than by rail. Passenger numbers on the “Dasher” decreased due to a bus service between Leighton Buzzard and Dunstable and an increase in car ownership.

In 1962, the passenger service between Leighton Buzzard and Dunstable came to an end. The last passenger train ran on 30 June 1962 and carried nearly 300 passengers. The line was axed under the plan for the railways drawn up by Dr Beeching.

General freight movements on the Branch Line ceased in 1966. Sand movements to and from Grovebury Sidings continued until 8 February 1967.

In 1969, the Leighton Buzzard-Dunstable Branch Line was closed down and most of the track dismantled. Some of the old buildings and parts of the track remain to be seen along the route, but housing estates and new roads cover much of it. In some places, the route became a cycle path or a footpath. A group of citizens is at present campaigning for the branch line to be rebuilt.

Within Leighton Buzzard many sections of footpaths and cycle ways follow the track bed, but much of it has been built on.

The new Leighton Buzzard by-pass, the A505, follows the old railway line. The remainder of the Stanbridgeford to Dunstable line is now National Cycle Route number 6.

The Sewell Cutting is a nature reserve run by the local Wildlife Trust. Many features of the line are still to be seen including some of the crossing keepers’ cottages, now private houses, and the bridge across the canal.

Light Railway

Moving materials within the sand pits was a difficult task using wagons drawn by horses.

When the weather was bad, the tracks within the pits became muddy and waterlogged. The sand soon turned to quicksand making hauling the wagons almost impossible as the wheels sank in. At first, wooden tramways would have been laid down to run the wagons on.

As technology progressed, these were replaced by iron tracks. These were not bedded onto the ground and could be moved around the pits to where the wagons were needed.

As the quarrying increased, barrow runs were constructed going from one side of a pit to the other and supported by wooden trestles. These were used mainly for carting the clay overburden from the new areas of the quarry to a part of the pit, which had been worked out.

The demand for sand increased and was being hauled through the streets of Leighton Buzzard to the canal wharves and railway sidings for onward transport. Damage to the roads was immense and so was the cost to the pit owners in compensation for road repairs making quarrying less than viable. In 1892, it was proposed that a standard gauge railway should be built to join up the sand pits and connect into the existing railway network owned by the LNWR (London & North West Railway).

This came to nothing and the sand industry was in danger of collapsing. World War One changed all that and sand was in great demand from munitions factories requiring ever increasing amounts of sand for foundry. Supplies from Belgium were halted when Germany invaded. Leighton Buzzard sand was found to be suitable and enormous quantities were sent daily by rail and canal.

In 1918 local residents complained about the smoke from steam road tractors, but the Director of Factory Construction for the Ministry of Munitions of War decreed that the nuisance had to be tolerated as the sand traffic was of national importance.

These steam tractors also caused damage to the road surfaces en route to the canal or mainline railway. The government paid for the upkeep of the roads for the duration of the war. After the end of the War the sand companies were held responsible for repairs to the roads. Then it became obvious that a railway was needed between the pits to carry the sand to the Leighton to Dunstable Branch Line and hence onwards to the rest of the country.

The Leighton Buzzard Light Railway: The two largest quarry operators, Garside and Arnold, put a plan forward to build a narrow gauge railway and so the Leighton Buzzard Light Railway came into being, allowing sand to be carried to Grovebury Sidings and tipped into standard gauge wagons.

Work commenced in August 1919 and it was finished before the end of the year. It consisted of three and a half miles of track, and nine un-gated level crossings. The remit for the work stated that steep hills should be avoided and there should be no sharp curves. However, the contractor put in a gradient of 1 in 25 (Marley’s Bank) and two very sharp bends. They also used 25lb rail instead of a much heavy 30lb rail, and straight rails were made to bend round the curves. These cost savings were the cause of many accidents and derailments.

The original plan was for the sand wagons to be drawn along the narrow-gauge tracks by horse. However, at the end of the war, Hudswell Clarke steam engines, built for the campaign in Italy, were put up for sale and two were duly purchased. They did not prove to be fit for the job and as the sleepers used to support the tracks were made from untreated wood from local woodland, they easily caught fire. Also, the sand in the wagons became contaminated by black smuts given off by the coal-fired engines. Another problem with them was that their tanks held only half the amount of water needed for each trip.

Therefore, the locos had to stop at Swing Swang Bridge to top up the tanks from Clipstone Brook, which ran below. After only two years, the two engines were replaced by smaller petrol driven “Simplex” locomotives, brought back from the Western Front and sold off cheaply as war surplus. The petrol driven locos were eventually replaced by diesels. Heavy snow and ice sometimes impeded the running of the rolling stock, but the Simples locos were very reliable and suited to purpose.

The decline of the Light Railway

The decline of the LBLR began in 1955 after a national rail strike. Arnolds took a greater part in the running of the railway and eventually took it over in 1964. However, its days were numbered and with the closure of the Dunstable to Leighton Buzzard Branch Line, in 1969, sand ceased to be carried to Grovebury Sidings by rail. Although the locomotives continued to work within the quarries, by 1981 dumper trucks had taken over the work of the locomotives. The last commercial delivery of sand took place on 27 March 1977.

In the meantime, a group of enthusiasts had formed a preservation society and negotiated to run passenger trains over part of the LBLR, taking over the whole railway when the carrying of sand ceased. The first public train ran on 3 March 1968, and in 1969, the name of the railway was changed to Leighton Buzzard Narrow Gauge Railway and now runs from Page’s Park Station to Stonehenge Works.

The railway, although narrow gauge, has to comply with modern Health and Safety Regulations and Rules. A lot of work had to be carried out on the tracks for the safe running of the trains.

Source:

Narrow Gauge Tracks in the Sand by Rod Dingwall

Souvenir Guide to the Leighton Buzzard Railway

Chaloner Newsletters

Road

When sand was being transported in the 17th century the poor-quality road system of Leighton Buzzard consisted of pack horse tracks.

Cities were connected by old Roman roads plundered for their stone. The means of transport consisted of packhorses, carts and large wagons, most cattle and poultry were driven to local markets or towns, where the tracks and roads passed through clay areas they became impassable ‘sloughs’ of mud.

Sand was collected from the working face of the pit by local carters and delivered to building companies, tile and cement works, mostly in the centre of Leighton Buzzard.

When the Grand Junction canal came to Leighton Buzzard in 1800 the carting traffic increased to meet the demands of pairs of working boats each loading 20/30 tons to be delivered to London and the Midlands. The canal had a monopoly on transportation only for 38 years; the rail link came to Leighton Buzzard. By the end of the 18th century the roads were being further damaged by the solid tyres of steam engines and wagons.

World War One brought about several changes in the road transportation of sand. The demand for local sand increased to supply the munitions industry and to fill the shortfall in cheap sand from Europe. Consequently, the damage to the local roads was increased, fortunately the Government offered to pay the road maintenance for the duration of the war.

When the war ended in 1918 the sand companies and hauliers had to resume paying for road damage and quickly resurrected an idea for a local light railway first proposed in 1899, this had three big effects on sand transportation by roads.

First, the near monopoly of the horse carters was removed and this was reflected in the Leighton Buzzard Observer on Tuesday 2nd December 1919:

“The opening of the Light railway has sounded the death knell of a local institution-the sand carter – He was never loved and not likely to be lamented – He was generally young (15-18 yrs old) and hefty; a knotted muffler was his neckware; he wore his cap at a ‘don’t care ‘ angle and a fag end gave him a final touch of freedom and independence – He had the reputation for beating all records in the twin art of wearing out horses and roads. The war brought him to the height of his prosperity –Whilst lesser fry were called up he was protected –Saturday saw the dismissal of a big batch of carters – the 36 horses at the auction will not shed a tear.”

Then, there was a reduction in steam tractors which was also greeted with thankfulness-Leighton Buzzard Observer on Tuesday 11th February 1919.

“Leighton Buzzard has seen the last of the steam tractors. And there are few people. who are not devoutly thankful? The tractors worked Sundays and weekdays alike and people who had 5/10 ton loads of sand waltzing past their houses every few minutes of the day reached a speechless stage of indignation…Cottagers aver that whilst they lay abed on Sunday mornings the foundations rocked and that pictures and ornaments have been jarred off the walls and mantelshelves and broken”.

The third consequence of the Light railway was a considerable reduction in traffic through the town centre.

World War Two again produced a demand for local sand but by now the railways had displaced the canals and road transport was providing a ‘door to door’ service. Rail transport would have continued to expand but the rail strike of 1958 allowed road haulage to predominate. The decline in the canals and rise of road transport directly affected William Vaughn who worked canal boats for Arnold, Garside and then drove a range of vehicles for A.C. Biggs, and other local hauliers

With the end of the war, men with military vehicles were looking for new employment. One example of this was the R.K. Browning haulage company who started in 1947 with one ex- military vehicle. His son has traced the developments in sand transport from the early four wheeled tipper trucks of the fifties, the first pressurised tankers of the early sixties using dried sand which in the seventies could be blown directly into the filter beds of water treatment works or storage silos.

Loading methods for sand have progressed from shovelling in and out of open carts through hand bagging and tying of recycled hessian sacks to paper and plastic sacks filled automatically and palleted, then loaded by fork lift truck.

In the 21st century sand transport is being measured for its carbon footprint as much as the cost per mile. At least one sand producer is investigating the re-use of the inland waterways. Will we see the return of horse carters in the high street?

Explore the sands

View early aerial photographs depicting how quarrying has advanced across the landscape

Sandpit sites >

Contact Us

The Greensand Trust,

The Working Woodlands Centre, Maulden WoodHaynes West End, MK45 3UZ, United Kingdom

Phone: 01234 743666

Email: info@greensandtrust.org

Or send an enquiry below: