Working Lives

The sand industry has had a major influence upon the local community

The industry has also contributed considerably to the economic growth of the area by becoming a major employer from the 19th to the 20th century and developing a large workforce.

It is possible to trace the story of men working as dobbers digging by hand with the help of the horses and carts to transport the sand. Read about the first steam excavators, to diesel locomotives and the latest techniques to extract sand, including 40-ton dumper trucks and a sophisticated dredging machine especially made to extract sand from under water at Grovebury quarry, one of only two in the world.

Find out how sand processing has changed, from very primitive techniques to sophisticated modern techniques to wash, dry and grade sand for multiple uses.

The effect on the community is covered in these pages. The positive and negative aspects are highlighted through personal stories. These include positive aspects of economic development, happy childhoods spent around quarries and the lasting friendships of working men and women. Sadly, incidents and deaths in the quarries are also referred to, the result of few safety regulations in the early days of the industry.

Digging the Sand

In the early days of sand quarrying, the back-breaking task of digging out and removing the top soil, or overburden, and the excavation of the sand was carried out entirely by hand, by poorly paid workmen known as dobbers.

The overburden, or the top soil, was removed using a procedure called ‘untopping’. By standing on the top of the ledge, sand was scoped down (locally know as dobbing). Big chunks of sand fell to the bottom of the quarry where the wagons were; there it was easy to be shovelled away. Another method was to dig 20-foot horizontal channels by hand in the sand, just underneath the clay. The working face was supported by columns of sand which were left intact. When everything was prepared, the pillars were chopped away, causing huge amounts of the clay to come crashing down, as the workmen ran to avoid being caught in the collapse.

Wooden trestle bridges were often built across the quarry and used as barrow runs to make removal of the clay easier. On other occasions a ledge might be dug beside the clay on top of the exposed sand and tracks laid down. When loaded with clay the skips were pushed, or pulled by a horse, and the overburden disposed of in another part of the quarry.

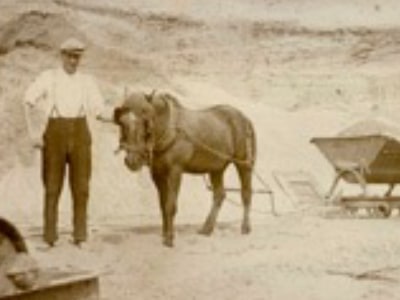

Horses were used in the heavy work in the early days of the sand quarries. Boys too young to become dobbers were employed as horse boys, tending to the horses before leading them to the quarry in time for the dobbers to start filling their skips with sand. The horse, led by one of the boys, would then haul one skip at a time from the quarry face, out of the pit and to the sidings at the end of the Leighton Buzzard Light Railway.

Horse boys often became dobbers when they were old enough to begin the dangerous job of cutting sand by hand and filling the skips at the quarry face. The dobbers would climb ladders up the side of the sand cliffs and once at the top would gouge out a tiny ledge, just wide enough to stand on, and begin to scoop the sand over the edge, ready to be shovelled into wagons waiting below. Often sand gave way beneath the feet of the dobbers and they would slip over the edge of the sand cliff, hopefully landing on the soft sand below!

Sometimes the dobbers took a dangerous shortcut to the digging process by undermining the sand to cause a collapse. The men would cut horizontal grooves in the base of the sand causing the whole face to slide down. When the sand started to slide, the men turned to face the oncoming sand and then dived to lay flat on top of it as it came towards them. Inevitably, some men were buried or crushed during these sand collapses. The risk must have seemed worth it to the low paid dobbers who were paid according to how many skips they filled in a day, generally up to about 30. They were also paid according to the type of sand excavated: more money could be earned for the more valuable sand.

Manual methods of sand excavation continued even after mechanical methods were available because it was an easy way for sand to be dug. During the 1930s the first mechanical excavators appeared, but hand-loading of the quarried material carried on in the Arnold quarries until the mid-1960s. Italian prisoners of war were used to dig sand in the Garside quarries and helped extend manual labour in these pits until 1945.

Machinery

During the 1930s mechanized excavation began to replace some of the manual labour in the pits.

Steam excavators on caterpillar tracks or road wheels began to be used to remove the top soil overburden. These machines were not energy efficient - they burnt a ton of coal a day and used 690 gallons of water - but their use meant that large amounts of sand could be uncovered quickly, to keep up with increased demand.

The first diesel excavators were introduced in about 1935. Ruston Bucyrus 10 RB excavators with face shovels attached were used extensively in the quarries to dig, and load sand into skips. These mobile and low-priced excavators could easily be converted to different equipment and easily transported from one job to another. Draglines on a 10RB were also used for excavation and comprised a long shallow bucket suspended by two ropes from a long lattice jib.

By the mid-1970s some pits were using hydraulic drag shovels with an inward facing bucket. The wire ropes had been replaced by hydraulic rams which controlled the jib, bucket arm and bucket. The real breakthrough in mechanized excavation came when rubber-tyred front-loading shovels were introduced to the quarries. These had an outward facing bucket on hydraulic arms, which could dig the sand, carry it within the pit and load the sand directly into the hoppers for processing, or onto a lorry.

Quarry excavation today in the 21st century is far removed from the early days of hard manual digging. Teams of contracted specialist overburden removers work for part of the year, removing overburden and exposing the sand, and skilled operators work the huge diggers that excavate the uncovered sand. At Garside’s Munday’s Hill Quarry a 360 degree long-reach digger with a bucket scoop works alongside three 40-ton dumper trucks. With efficient timing, the digger can keep the dumpers constantly supplied with loads of sand, to take to the on-site processing plant, before coming back for more.

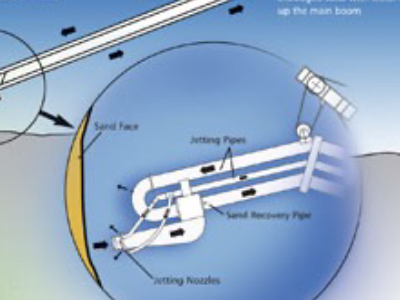

To the south of Leighton Buzzard in Garside’s Grovebury Quarry, sand is excavated from below the water table, an operation that requires special machinery. Originally, a steam grab crane mounted on a barge was used. Today sand is excavated from beneath the water using a suction dredger, one of only two inland dredgers working in the UK. Powerful water jets fire at the bottom of the sand face, below the water line. The sand and water mix is then sucked into a pipeline which stretches across the lake to the shore where it is pumped out and processed.

Processing Sand

Processing of the sand after excavation began as a basic procedure to remove grit and unwanted material but, when the uses for sand expanded, processing became more complex.

In the early days of quarrying processing was as basic as a casual throw of the sand through an angled sieve placed over the wagon that the dobber was loading.

Unwanted material fell to the ground and the sand dropped through into the wagon. When demand for sand increased in the early 20th century processing began to be mechanized. An early machine, known as a ‘shaker’, consisted of a vibrating mesh screen with 1/2 inch holes, ideal for screening coarse building sand.

Some customers began to want a more pure, more finely graded sand, so processing methods began to be refined. Also, higher prices could be asked for sand that was processed and so processing plants were established in or adjacent to the quarries.

Washing

During WW1 the foundries making armaments needed large amounts of sand free from impurities to make their castings, so the sand began to be routinely washed. In a machine known as a ‘Niagara’ the sand was washed by a stream of water on to a vibrating 1/2 inch mesh screen which removed larger particles like gravel. The finer sand particles fell through the mesh on to a 1/8 inch mesh screen made of piano wire, to further refine it. The refined sand was washed into a tank where it was stirred, and the silt pumped away. A bucket conveyor then lifted the sand from the washing tank to a chute which fed the waiting wagons. The buckets were perforated to allow excess water to drain away; the wagons also had holes in the bottom for further drainage.

The ‘Niagara’ was later replaced by barrel washers which worked on much the same principle but the sand was fed by conveyor into slowly revolving drums containing sieves of varying mesh size. Water for washing came from deep pools at the washing plant.

Modern quarries use attrition scrubbers which remove silt and gravel from the sand particles using the abrasive power of water and hydro-cyclone systems, which in turn use pressurized water jets to float the fine grains of sand away from the coarse grains. Solid particles that are separated from the finer sand particles are allowed to settle in silt lagoons. Mindful of recycling and energy efficiency, the silt can be reused in quarry restoration and some of the water can be reused for washing.

Drying

In the early days of the quarries, sand was transported to the customer in its wet form, but there began to be a demand for a dry product that could be used immediately. At the processing plants, drying sheds housed large coal-fired ovens for this purpose. In a modern processing plant a system of conveyors feed the wet sand into gas and oil fired dryers, each costing £750,000.

After it is dried, the sand is graded to produce the grain size needed for a particular purpose. Vibrating rotex screens made from metal or plastic are used to screen the sand; these can be changed to produce the different grain sizes. In a modern processing plant many different grain sizes can be selected. The graded sand is then conveyed to storage silos or on to a bagging shed. The whole operation is controlled from a central diagnostic desk, controlling flow and storage.

The sand is tested several times at various stages of the process to ensure that it conforms to the specifications of that particular grade of sand.

Once washed, dried, graded and tested the sand is bagged ready for transportation. In the old days hessian sacks were filled by hand in a bagging shed and teams of women employed to mend them. Old coffee sacks were often used and one worker remembers a woman being employed to turn the sacks inside out so that the sand would not be contaminated with coffee. Today’s bagging operation is very different: robotic bagging systems reduce all the manual labour to the touch of a button. The correct weight of sand is deposited into each polythene sack, which is sealed and sprayed with a batch number, date and grade and moved by forklift truck to the waiting lorries.

Specialist Processing

In the modern sand industry customers often require a product that needs special processing. This may take place on-site or be done by specialist companies. Organic pigments may be added, for example, to colour the sand for use in sports pitches and arenas.

A specific terracotta colour often used in sporting arenas is achieved by burning the sand. In other uses, for example in the manufacture of colourless glass, complex processes may be needed to remove certain stubborn particles. These can involve hot sulphuric acid leaching to remove iron and iron oxides. Soil may be added to the sand for use in horticulture, something which is done on-site at Garside’s Grovebury quarry.

Communities

The Leighton Buzzard, Linslade and Heath and Reach areas are geologically rich in sand.

Sandpits appeared everywhere, providing continuity of work for many families and affecting the lives of local people in a positive, as well as a negative way.

Work

The men worked in all the various processes involved in extracting, cleaning, processing and transporting the sand. Women were also employed in the offices and in mending the hessian sacks which held the sand. Maureen Gurney describes how her mother, great aunt and a friend, all from the same street in Heath & Reach, worked sewing hessian sacks. She also talks about the building where they worked

Sands of Time Trail 8: Mum’s job sewing sacks in the drying by Maureen Gurney (02:45)

Explore the sands

View early aerial photographs depicting how quarrying has advanced across the landscape

Sandpit sites >

Contact Us

The Greensand Trust,

The Working Woodlands Centre, Maulden WoodHaynes West End, MK45 3UZ, United Kingdom

Phone: 01234 743666

Email: info@greensandtrust.org

Or send an enquiry below: