Geology

Bedfordshire lies over a geological feature of Great Britain which runs in an arc from roughly the Wash to the Isle of Wight.

Its geology is varied and complex and a great deal of related information is available at the county’s geological website Bedfordshire Geology group where specific leaflets can also be downloaded. Our grateful thanks are owed to the Bedfordshire and Luton Geology Group for their assistance in preparing the accompanying pages.

Sands were laid down from around 115 million years ago as, after 40 million years as dry land, the area suddenly became flooded by the sea, water bursting across what is now southern England, forming a narrow channel running south west from the Wash, across to the Isle of Wight. The sand accumulated over a long period of time during which many interesting features developed which careful analysis has been able to detect.

The sand beds later became capped by layers of clay deposited when, following further geological changes, the area became the bottom of a tropical ocean giving rise to a further accumulation of fossils. Subsequent erosion, mainly by glacial ice, has scrubbed away the accumulated geology in some places.

Removing the clay and making use of the sand (in industrial applications) revealed further potential from the fossil and coprolite resource revealed during earlier quarrying of these resources.

Formation

The Lower Greensand Formation outcrops from Hunstanton in Norfolk, through Cambridgeshire, Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire and southwards to the Isle of Wight.

Its sediments comprise a set of sands, sandstones, silts, clays, and ironstones that change in character across the region. They were deposited in the early Cretaceous from c. 115 million years ago a period known as the Lower Cretaceous. The sands within it are up to 120m thick in total and fill a 25-30km wide trough trending Northeast – Southwest.

The quarries of Heath & Reach, Bedfordshire are among the best places in England to view and interpret the features preserved in the Lower Greensand. Stone Lane Quarry shows us three units of Lower Greensand which rest on a phosphate pebble base.

The phosphate pebble bed found at the base of the Lower Greensand from Great Brickhill (Bucks) to Potton (Beds) and Upware (Cambs) is evidence of an early pulse of the sea-level rise that eventually flooded this region. These reworked phosphatised marine fossils were one of the ‘coprolite’ beds exploited for fertiliser production during the late 1800s to early 1900s.

The lowest, Brown Sands, were laid down over the phosphate beds in the seaward end of an estuary. They are strongly iron-stained and full of the burrows of shrimp and other animals, which stick out of the sand face like tiny drain pipes, preserved by an inner coating of hard ironstone. The Brown Sands contain Seams of Fuller’s Earth (a bentonite clay derived from re-worked ash) which are evidence of volcanic eruptions in north-west Europe.

Above the Brown Sands are the Silver Sands, showing “cross-stratification” in beds that may be over 1m thick. These were large dunes forming a sand bar at the mouth of the estuary.

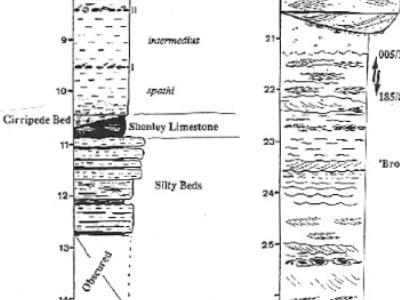

Above these is the Silty Beds, a unit containing many different thin, flat beds of silts, sands, clays and ironstone. The sand layers were the lower flats, while the muds were deposited in the back lagoons.

Throughout the Woburn Sands area there are signs that currents and tides moved the sands back and forth. These movements built up many thin layers of sand to form dunes on the seafloor; We see the pattern of those layers when cliffs and quarries display sections through the dunes. All the sands are cemented together by iron oxide (rust!). Sometimes there’s enough iron oxide to bind the sands into hard brown sandstone.

As geological time progressed, all of Britain came to lay at the bottom of a warm tropical ocean. The Gault Clay tells us something of this, but about 95 million years of the story are missing, eroded by the ice that deposited a thick layer of till on top of the Gault.

With the further passage of time and geological activity, sea levels declined and dry land appeared, from time to time to be covered by the glaciers of several ice ages. Glacial erosion produces ‘till’ as the glaciers ground their way across the surface. The latest glacial period ended about ten thousand years ago. Till is a mix of materials scraped from rocks by the glacier. The till here is almost Gault-grey, but includes pebbles of flint and Chalk, as well as fossils such as Gryphaea from the Jurassic Oxford Clay. The fossils are in good condition, so they did not travel far under the glacier.

Sand Features

These sands can be divided into distinct types. Working downwards from the surface and underneath till created by glaciers and Gault clay, one first encounters beds of Silty Sands

The Red Sands; then the Silver Sands; and finally the Brown Sands at the lowest level beneath which is a Phosphate Pebble Base. Each tells us about a different episode in the story of the flood. Within the bands of sand, Cross-stratification can be seen, which gives an indication of the conditions under which the sand was laid down – even the formation of Sandstone.

Sand Features GALLERY

Tap an image below to view

Shenley limestone

Shenley Limestone – General

.Shenley Limestone is a very rare and small formation that developed in a geographically small area around Shenley Hill in Leighton Buzzard.

It appears that eroded remnants of the Silty Beds formed low mounds on the sea floor. A gritty ironstone capped these mounds and thin lenses of limestone formed between them – the Shenley Limestone. It is a pale fawn brown phosphatic limestone with scattered polished goethite balls. The formation is noted for its rich and varied fauna of brachiopods and rare ammonites.

Nine Acre Pit was designated by Natural England as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) for its exposures of Shenley Limestone. However, it has been noted that this formation does not actually outcrop on this site but in the neighbouring quarry, Mundays Hill.

Shenley Limestone – Composition

Shenley Limestone is only found in the Heath & Reach area, in the uppermost levels of the ironstone horizon within the Silty Beds.

It is a bioclastic limestone filling cavities in the topmost ironstone. It is a highly unusual micrite, full of poorly sorted clasts (pebbles and sand) and many fossils, largely cementing/attaching animals such as bryozoa, brachiopods or serpulids, with abundant echinoid spines and rare (possibly reworked) ammonites.

Shenley Limestone is a marine deposit, a very near-shore accumulation resulting from still water deposition (micrite) with high energy currents or waves adding pebbles and debris.

Clay and Fossils

The Lower Greensand of Bedfordshire is informally divided into the Red Sands and Silver Sands (Upper Woburn Sands) and the Brown Sands (Lower Woburn Sands), further information is available on the Formation & Sand Features section above.

The sands are up to 120m thick and fill a 25-30km wide NE-SW trending trough. The formation also includes, in the upper horizons, Silty Beds up to 10m thick, in which the uppermost ironstone horizon contains the Shenley Limestone, as shown in the diagram below.

Within the Lower Greensand deposits of till, clay and the various horizons of sand, a variety of fossils are to be found.

Glacial Till

The Gault Clay tells us something of the period when all of Britain lay at the bottom of a warm tropical ocean, but about 95 million years of the story are missing, eroded by the ice that deposited a thick layer of till on top of the Gault.

The till, which itself is almost Gault-grey in colour, contains a mix of materials scraped from rocks by the glacier, but includes pebbles of flint and Chalk; Worn, reworked fossils from the Gault, where it has been previously eroded and carried forward by glacial movement; Fossils such as Gryphaea from the Jurassic Oxford Clay. The fossils are in good condition, so they did not travel far under the glacier.

The Gault Clay

The Gault Clay which caps the layers of sand was deposited at the bottom of a tropical ocean. There are lots of tiny marine fossils in this clay, including ammonites, belemnites (little squid) and bivalve shells.

The clay horizons have been analysed for palynoflora, which proved to be particularly rich in brackish species and terrestrially-derived pteridophyte spores, with some freshwater algae. This evidence, together with the sedimentary structures, indicates a near-shore estuary mouth location.

The Silty Beds

The Silty Beds which appear only in the Heath & Reach area include pale sands laid down in fast currents as well as fine-grained organic sediments rich in fossils.

The Red Sands

The base of the Red Sands shows trace fossils including Planolites, Teichnichus, Skolithus, Ophiomorpha, Macronichus and echinoid burrows. Sedimentation was too rapid later on to allow organisms time to burrow. In Stone Lane Quarry is the Cirripede Bed, which lies under the Gault in the southwest corner of the quarry. The bright red sediments contain many fossils, including barnacles, oysters, fish teeth, icthyosaur bones and corals.

The Silver Sands

The Silver Sands contain abundant fossils of wood, largely from cycads, tree ferns and pteridophytes. The wood is preserved in several different ways: charcoal (indicating forest fires), lignite (often in pyrite coated nodules, testifying to rapid deposition), limonite or haematite cemented nodules, and tree trunks.

Evidence of the newly evolved angiosperms is a very rare occurrence in the Aptian fossil record, which makes the search in these sands particularly exciting!

The Brown Sands

They are beige in colour, fine-grained with quartz grains (pale), many mica flakes (silvery and shiny) and occasional black rock fragments. You may also see hard ironstone horizons (iron pan), and many fossil burrows dug by worms, shrimps and other animals living in the estuary. They commonly include limonite cemented wood fragments and other iron nodules and iron pan horizons.

The Brown Sands are also notable for abundant trace fossils including Taenidium, Siphonites, Planolites, Rhizocorallium and Teichnichus. Within the Brown Sands lies a layer of Fullers Earth.

Fullers Earth formed from layers of ash vented by Cretaceous volcanoes, probably in northwest Europe, but possibly west of the UK under what is now the Atlantic. Buried at just the depth, the ash changed chemically over time to become Smectite clay. The slopes of the Greensand Ridge are among the few places in Britain where Fullers’ Earth is found.

The Phosphate Pebble Base

The phosphate pebble bed found at the base of the Lower Greensand from Great Brickhill (Bucks) to Potton (Beds) and Upware (Cambs) is made up of reworked phosphatised marine fossils.

These were one of the ‘coprolite’ beds exploited for fertiliser production during the late 1800s to early 1900s.

Coprolites

‘Coprolite’ comes from the Greek word kapros and lithos, meaning ‘dung’ and ‘stone’. Real dinosaur dung dating from the Jurassic period is found in Britain, but the coprolites of Bedfordshire, Cambridgeshire, Hertfordshire and Buckinghamshire are nodules of phosphate-rich Cretaceous sediment, often containing fragments of fossils.

Rising sea levels due to global warming in the Lower Cretaceous period created a seaway, running southwest from the Wash across Bedfordshire and on toward the Isle of Wight. The currents and tides washed ammonites and other fossils out of the Jurassic clays.

These worn, rounded fragments were deposited into areas with high levels of phosphate from dead shellfish and other animals. The nutrient-rich sediments coated these derived fossils (derived from other sediments) to form concretions while calcium phosphate slowly replaced the calcium carbonate of the fossils.

Burrows of animals living in the seafloor filled with sediment: the casts are known as trace fossils. Both trace and derived fossils are known as coprolites when they are mined from the Gault Clay and the Woburn Sands.

Clay and Fossils GALLERY

Tap an image below to view

Explore the sands

View early aerial photographs depicting how quarrying has advanced across the landscape

Sandpit sites >

Contact Us

The Greensand Trust,

The Working Woodlands Centre, Maulden WoodHaynes West End, MK45 3UZ, United Kingdom

Phone: 01234 743666

Email: info@greensandtrust.org

Or send an enquiry below: