Sandpit Sites

Extraction of the sand has contributed to the discovery of some of the evidence of early man's occupation. We owe many thanks to local enthusiasts like Bernard Jones and the late Frederick Gurney who was always at hand to make meticulous recordings.

Leighton Buzzard sand industry has continued for over 150 years. Sand extracted from the local pit is exported all over the world and has many vital uses.

Interviews with people involved in the industry have provided fascinating and valuable information about the companies, working lives, and about how the sand was extracted and the machinery and processes involved. We’ve discovered more about the history of the early days of back-breaking shovelling, carried out by the sand ‘dobbers’ and the use of horse-drawn carts to remove the sand, through to the introduction of mechanical excavators, screening and washing equipment and the arrival of the light railway.

Mechanised means of loading the sand into wagons were more recently introduced, after which it would be transferred to the main railway line for onward transport to all parts of the country and abroad. Sophisticated industrial equipment is now used and sand is moved by road.

Well-known names in the sand industry are prominent in Leighton Buzzard and Heath and Reach. Garside Sands has been a familiar name, offering local employment for several generations. Arnold was also destined to become a well-known name in the local sand industry, following the establishment of a business formed by John Arnold in the 1860’s. The Jones’ family quarried sand after World War two and had three operational pits in the later 1960’s and LB Silica Sand Ltd is still trading locally too.

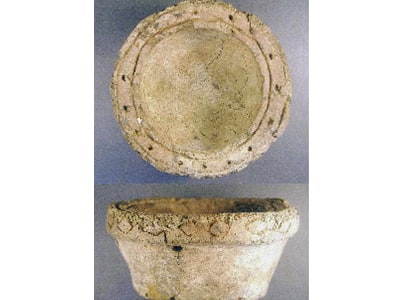

Archaeological evidence

Tap an image below to view

Man has lived in the British Isles for many thousands of years and there is evidence of existence in Leighton Buzzard for much of that time. That evidence is only revealed by scrutiny of the soil for debris scattered because of activities. Some evidence is highlighted in this summary, further investigations continue by the Archaeological Society, reported in its annual newsletter ‘Transactions’.

Changing Landscapes

What happens to the land when sandpits close?

Spinney Pool

South East of Firbank Pit, at right angles to Billington Road, south of Leighton Buzzard was Spinney Pool pit. It was opened by Joseph Arnold & Sons Ltd in the 1880s, and closed towards the end of World War One.

In the summer of 1921 Leighton Buzzard Swimming Club was formed by Mr Raymond Willis and Mr G Stockwell. The worked-out Spinney Pool pit had filled up with spring water and the Swimming Club rented the pool from Arnolds for £100 per year. This freshwater pool measured some 300 yards by 50 yards and was up to 40 feet deep in places. Several diving boards were built; the highest, in the deepest part of the pool, was at 36 feet from the water surface. With landing stages and changing huts national swimming and diving events were held, attracting up to 3,000 visitors.

Children were taught to swim in the shallow waters of ‘The Crib’, a wooden platform with a protective fence around three sides.

Swimming was not without risk; the pool depth was irregular and shelves of sandstone protruded from the side of the pool, beneath the water level. Several drowning were reported.

In 1932 the Swimming Club purchased the pool for £600 and successfully ran it until 1946. Annual swimming galas on August Bank Holiday Monday afternoons became popular events, followed by a dance carnival evening, raising money for hospitals in the area.

The pool gradually dried up between 1939 and 1947. After the end of World War Two, truckloads of London domestic rubbish were carried by train to fill in the pit. The site is now part of an industrial area.

Nature takes over former Quarries

Living in Heath & Reach for twenty-seven years, next to a corner of Sheepcote Quarry, I have seen a lot of changes. When we came, Sheepcote Quarry was a huge hole around 60ft deep. It is now filled in, grassed over and a haven for wildlife – foxes, deer, badgers, the occasional slow worm and a tawny owl that roosts in our oak tree, to name a few.

Part of Stone Lane Quarry now forms Heath & Reach Sports Association field, though the footpath that used to cross it has yet to be restored – nevertheless a far cry from when Bryants Lane was closed while stabilisation work was carried out to prevent the lane falling into the quarry.

Parts of Bryant’s Lane and Reach Lane Quarries are now inactive, and while I regret the loss of paths that used to cross them (and the superb blackberries that grew there), the footpaths and hedges around the quarries have become home to a huge range of wildflowers, birds, and animals, some of which are quite rare (bee orchids, small tortoiseshell butterflies, and several cuckoos for example). As restoration continues, hopefully the wildlife will continue to flourish, and we will get our footpaths back.

Pauline Hey

Tiddenfoot Waterside Park

During the Jurassic period, Tiddenfoot lay under a warm, shallow sea, full of ammonites, oysters, fish, ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs.

In the Cretaceous period sea creatures thrived and dinosaurs roamed dry land. Rivers washed sand into the seas. Tiddenfoot was a beach of mud and sand, which became the Lower Greensand. As time passed, sediments (Gault clay, followed by chalk) were deposited over it.

About 20 million years ago, Africa collided with Europe and the Greensand Ridge was formed. Tiddenfoot was near the southern end of the ridge.

The climate changed about 2.6 million years ago, Earth entered the Ice Age. The country was covered with a sheet of ice, which, scraped away at the land, stripping the chalk and softer clay deposits, revealing the sands of the Greensand Ridge. During interglacial periods, grass, trees and shrubs grew. Tiddenfoot may have become the hunting ground for early man, chasing after elephants, great deer, and mammoths.

In prehistoric times, on a route known as Theodweg was where travellers crossed the River Ouzel. 2000 years ago, the Romans established Theedway as a salt route from the midlands to the south.

A thousand years later the Saxons were at war with the Danes. The Saxons had improved the Ouzel River and called it Yttingaford, and it was here in 906AD that Edward the Elder, made peace with the Danes. Eventually the old salt route fell into disuse. Only the name Tiddenfoot remains.

1800 saw the construction of the Grand Union Canal with a wharf at Tiddenfoot. From 1920 to 1960, Tiddenfoot Pit was quarried by The London Brick Company, the sand carried by Canal Boats across the country. When the pit closed nature took over; plants and wildlife established themselves. The pit became a lake. The site was owned and managed from 1976 by Bedfordshire County Council, from 2009 is owned and managed by Central Bedfordshire Council.

The Greensand Trust now manages Tiddenfoot Waterside Park. Volunteers help maintain the grassy areas, woodland, lake and ponds. People enjoy walking and cycling, and Leighton Buzzard Angling Club members fish in Tiddenfoot Lake. A Waterside Festival is held annually with something for everyone: music, narrow boats, arts and crafts and stalls of all kinds.

The eight-acre lake at the centre of the park is home to many animals such as fish, frogs, toads, dragonflies, damselflies, and other aquatic insects. Resident and migratory birds abound too, such as Great Crested Grebes, Tufted Ducks, Mute Swans, Coots, Moorhens and Kingfishers. sand martins race along the lake feeding on insects. Trees and shrubs provide food, shelter, and nesting places for many birds.

THE SAND QUARRY “WINFIELD’S PIT”

The quarry under the current northern and western rim of the Course, was called Winfield’s Pit. It was opened in 1953 and provided sand, mainly for the building industry, until it was exhausted by the end of 1979. The quarry was back-filled progressively, initially to approximately road level. However, the last and largest area to be quarried was back-filled to roughly match the previous land profile. Quarrying activity obscured, demolished or affected certain historic features of the landscape and notes are incorporated on these topics below. Further information and the maps and photographs from which the information is derived can be referenced in Bedfordshire County Archives or Leighton Buzzard Library.

STONELEIGH ABBEY

Stoneleigh Abbey, or Stoney Abbey as it is sometimes known, was never an Abbey, nor did it have any monastic connections. The manorial lords from the 17th to 19th century, were the Leigh family who hailed from Stoneleigh Abbey in Warwickshire. This was one of their properties in this area and it is presumed that the name was coined by association, familiarity or whatever. Although the house was demolished in the 18th century, its name lived on at that site.

AN IRON AGE ENCLOSURE “Craddocks Camp”

It is generally accepted that an Iron Age Enclosure, associated with the name “Craddocks” covered the majority of the area occupied by holes 1 to 9 of the golf course. It consisted of a single bank and ditch earthwork enclosing a considerable hilltop area. Most of the earthwork evidence of the Camp has been lost after such boundaries were removed following the land enclosures of the 1840s. The name ‘Craddock’s has been consistently associated with this area, and is likely to have been sustained even from as far back as the original Iron Age Camp itself.

AN ANCIENT HOLLOW WAY “Craddock’s Way”

Central across the golf course, running north, is a sunken gully or hollow way, now occupied and surrounded by trees and bushes. It fell into disuse following the period of enclosures and now remains a concealed element of our transport heritage although its name continues to give an insight into its history.

TWO TRACKWAYS LOST UNDER THE GOLF COURSE:

Phillips Track-way.

An early (1848) Map of Heath and Reach shows a new private road leading from Linslade Road, up to a parcel of land owned by ‘Phillips’. Any evidence of the existence of this has apparently been lost underneath the Golf Courses and its renovations.

A Trackway Eastwards Round Rushmere Manor.

Bryant’s 1826 Map of Heath and Reach shows a pathway, commencing on what is now called Plantation Road - probably at the crest of the ridge, running down to the east of Rushmere Manor, to join up with Linslade Road. No evidence of that track-way apparently now remains.

A SHEPHERDS MAZE

R Richmond, writing in his 1928 book ‘Leighton Buzzard and its Hamlets’ cites the existence of a Shepherds Maze, the remains of which were “some 200 yards south-east of the site of the house known as Stoneleigh Abbey, and on the other side of old Craddock’s Lane. His directions would place the Maze roughly along the current 5th fairway of the golf course, on its north face some yards down the slope from the crest of the rise.

ROADS CALLED: “THE STILE” & “ABBEY WALK”

Following quarrying, house-building commenced adjacent to Winfield quarry. Two of the roads providing access to the new houses were given names which preserved the name of a local footpath (The Style) and the building (The Abbey – ie Stoneleigh Abbey) that had become casualties of the quarry’s excavation.

SOME NOTES ON EMU FARM AND EMU PIT

There is no record of the name ‘Emu Farm’ prior to 1910; Bedfordshire Community Archives web pages concerning Heath & Reach. Indications are that the unusual ‘Emu’ name emerged in 1910. The reason behind this unusual name remains to be discovered. Beside and behind the farm, to its left, a 1946 aerial photograph reveals a small quarry, presumed to be Emu Pit or sand quarry.

Explore the sands

View early aerial photographs depicting how quarrying has advanced across the landscape

Sandpit sites >

Contact Us

The Greensand Trust,

The Working Woodlands Centre, Maulden WoodHaynes West End, MK45 3UZ, United Kingdom

Phone: 01234 743666

Email: info@greensandtrust.org

Or send an enquiry below: